| 發表文章 | 發起投票 |

8/6:Hiroshima, Life after the bomb

Sunday 6 August 2017 08.00 BST

The Guardian[/size=2]

https://www.theguardian.com/science/brain-flapping/2017/aug/06/life-after-the-bomb-exploring-the-psychogeography-of-hiroshima[/size=2]

[/center]

[/center]

Hiroshima is flourishing. It has a population surpassing 1.19 million, a burgeoning gourmet scene, towering luxury shopping centres, and a trendy night life. It is a city of vibrant green boulevards and open spaces, entangled by the braided tributaries of the Ōta River. However it is also a city of memorialisation. Over 75 monuments, large and small, sprout like delicate mushrooms in parks and on sidewalks, scattered across the city as if by the wind. Whilst the city grows and evolves, the memory remains of Hiroshima as first place on Earth where nuclear weapons were used in warfare, on 6 August 1945.

The number of fatalities is not known, due wartime population transience and the destruction of records in the blast. Estimates are in the region of 135,000 people, roughly equivalent to the population of Oxford. It is therefore unsurprising that many locals have Hibakusha veterans in their families. The Hibakusha community maintain a living collective memory of the bomb, sharing their atomic folktales similarly to the Kataribe storytellers, as a cautionary modern mythology against nuclear war.

It was assumed that nothing would grow within the bleak 1.6km blast-zone for 75 years. However, surrounding prefectures donated trees to Hiroshima. Fresh stems quickly pushed through the damaged earth, plants took root, and the branches of the Hibaku-jumoku, the survivor trees, unfurled leaves of weeping willow and oleander from budded stalks. The city has been rehabilitated, and it is challenging to imagine it as a place of devastation. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is a lush focal point of this re-greening process, and a unique human ecosystem has sprung up among the gingko trees and sussurating cicadas.

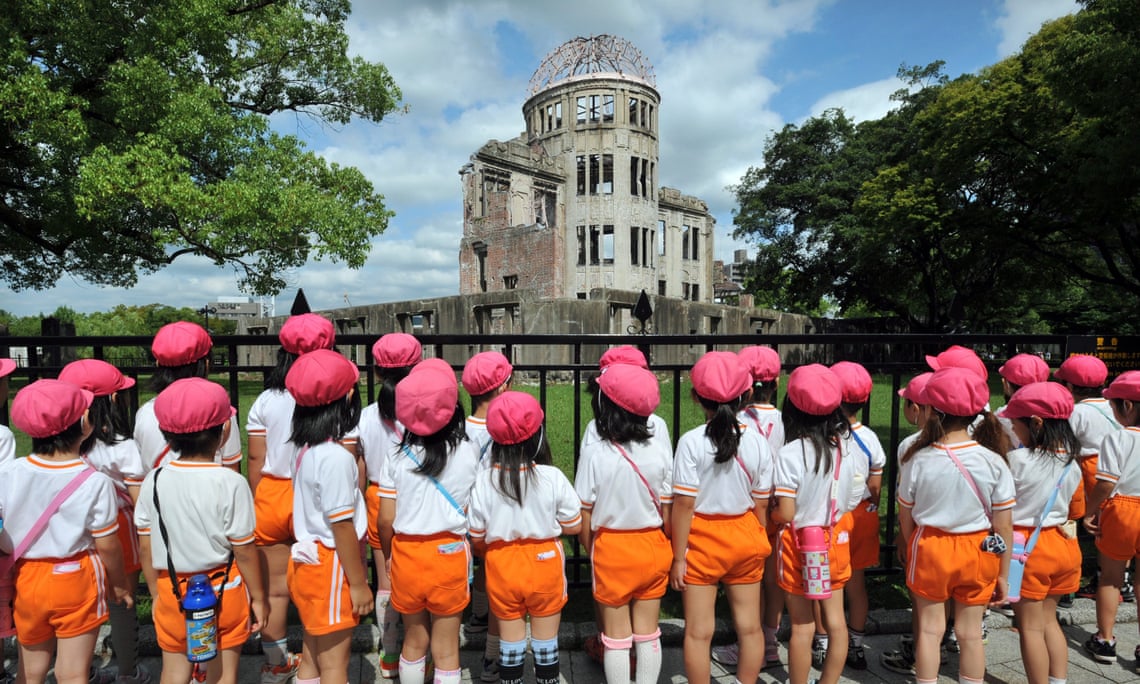

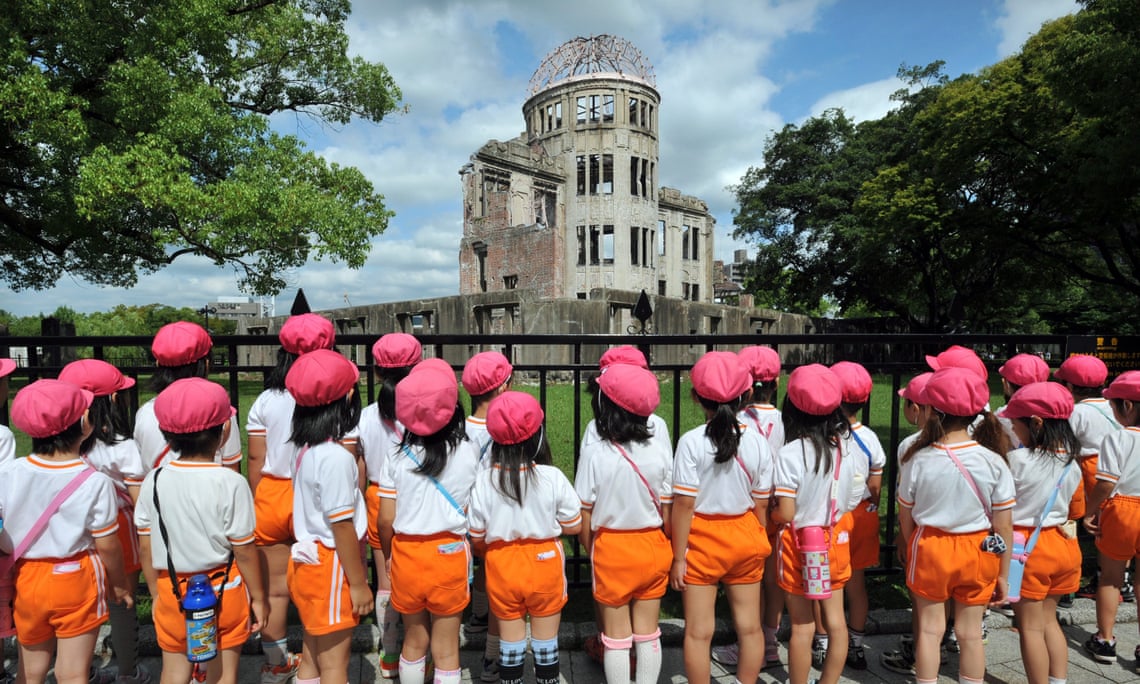

The park has its own distinctive psychogeography, providing a public space for complex emotions and experiences to be explored by locals and tourists. International visitors feature prominently around the larger memorials and cenotaph. They ring the delicate origami crane bell-pull within the Children’s Peace Monument, take a few photographs of the cenotaph, stroll beside the Peace Pond, and then across the river to the A-bomb dome.

Distance is no indication of personal connection, and victims of Hiroshima have originated from across the USA, China and South East Asia. Thousands of Koreans died in Hiroshima: the men were forcibly conscripted and the women performed the duties of “comfort women”. The monument and Cenotaph to Korean Victims are festooned with brightly coloured flowers and receive a constant trickle of visitors, many of whom are Korean. Swags of peace cranes garland the smaller memorials dotted about the park, and the fragrance of sandalwood and citron lingers, as incense is lit and local heads are respectfully bowed. Japanese schoolchildren come here to learn, and they sit in the shade of the trees at noon in civilised huddles, to eat lunch and chatter.

Many visit to reflect upon the atrocity of the bombing, but this attitude is not universal. I learned this during an encounter with an American man at the Ground Zero memorial, tucked away on a side-street beyond the boundaries of the park. We smiled at each other, as he shared his reasons for visiting, declared the power of the bomb to end the war, and the American soldiers, including his grandfather, whose lives were saved by this action. He was grateful for the bomb, but I was shocked at the way he had decided to make an emotional connection with this place.

However, the local community has a deep and profound connection to the park. Volunteers in distinctive uniforms meticulously maintain the place on a daily basis. This voluntary care of space escalates, as Hiroshima Peace Day draws near. Visit the park at 6am towards the end of July, and you will discover hordes of elderly people from the “Senior University”, wearing sunhats and brandishing trowels. They crouch above the ground, plucking weeds from the soil with gloved fingers. Whilst they garden, trails of elegantly dressed office workers bisect the park at intervals, carrying files and parasols in delicately gloved hands. Commuting to work, this stretch of land has become another familiar part of the rhythm of their daily lives.

There are also spaces of conflict and deviance here. The Uyoku dantai are the Japanese extreme-far right. They call themselves the Society of Patriots and travel about in dark vans painted with worrying slogans. War crime denialists, they support historical revisionism, oppose socialism and want Japan to join the nuclear circus. Unfortunately, they cannot be arrested due to the protection of freedom of ideology by the Constitution of Japan. So they jeer from the sidelines of the park, and organise protests outside the A-Dome on Hiroshima Peace Day. To the consternation of many, they have been gaining popularity in recent years.

However, there is also a place of joy hidden within this park, on a dusty corner of dry earth behind the public toilets. Here, a group of elderly Japanese men meet every week-day morning, to crouch on battered wooden chairs and play board games. Some, but not all, are Hibakusha, but all of them look relaxed, and laugh loudly as they engage in drawn-out battles of Shogi and Go. They have created their own friendly-yet-private space within this park. As dusk sets in, they pack up their board games and fold up their little chairs and tables to go home. The cicadas grow louder, and a calmness settles over the park as twilight descends. Small clusters of local teenagers gather and relax in the evening’s warmth. Faint sounds of conversation gradually dwindle to nothingness and the day draws to a close, reclaimed by the stillness of night. Our day in the park may be over, but the collective memory of the Hiroshima bombing forever remains.

With gratitude to Professor Bo Jacobs at Hiroshima Peace Institute, and with love to the extraordinary Hibakusha of Hiroshima and their families worldwide.

Becky Alexis-Martin is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Southampton, with expertise in the cultural and social effects of nuclear defence. She writes on the lives of nuclear test veteran families, and the cultural and social significance of nuclear places and spaces.

The Guardian[/size=2]

https://www.theguardian.com/science/brain-flapping/2017/aug/06/life-after-the-bomb-exploring-the-psychogeography-of-hiroshima[/size=2]

[/center]

[/center]Hiroshima is flourishing. It has a population surpassing 1.19 million, a burgeoning gourmet scene, towering luxury shopping centres, and a trendy night life. It is a city of vibrant green boulevards and open spaces, entangled by the braided tributaries of the Ōta River. However it is also a city of memorialisation. Over 75 monuments, large and small, sprout like delicate mushrooms in parks and on sidewalks, scattered across the city as if by the wind. Whilst the city grows and evolves, the memory remains of Hiroshima as first place on Earth where nuclear weapons were used in warfare, on 6 August 1945.

The number of fatalities is not known, due wartime population transience and the destruction of records in the blast. Estimates are in the region of 135,000 people, roughly equivalent to the population of Oxford. It is therefore unsurprising that many locals have Hibakusha veterans in their families. The Hibakusha community maintain a living collective memory of the bomb, sharing their atomic folktales similarly to the Kataribe storytellers, as a cautionary modern mythology against nuclear war.

It was assumed that nothing would grow within the bleak 1.6km blast-zone for 75 years. However, surrounding prefectures donated trees to Hiroshima. Fresh stems quickly pushed through the damaged earth, plants took root, and the branches of the Hibaku-jumoku, the survivor trees, unfurled leaves of weeping willow and oleander from budded stalks. The city has been rehabilitated, and it is challenging to imagine it as a place of devastation. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is a lush focal point of this re-greening process, and a unique human ecosystem has sprung up among the gingko trees and sussurating cicadas.

The park has its own distinctive psychogeography, providing a public space for complex emotions and experiences to be explored by locals and tourists. International visitors feature prominently around the larger memorials and cenotaph. They ring the delicate origami crane bell-pull within the Children’s Peace Monument, take a few photographs of the cenotaph, stroll beside the Peace Pond, and then across the river to the A-bomb dome.

Distance is no indication of personal connection, and victims of Hiroshima have originated from across the USA, China and South East Asia. Thousands of Koreans died in Hiroshima: the men were forcibly conscripted and the women performed the duties of “comfort women”. The monument and Cenotaph to Korean Victims are festooned with brightly coloured flowers and receive a constant trickle of visitors, many of whom are Korean. Swags of peace cranes garland the smaller memorials dotted about the park, and the fragrance of sandalwood and citron lingers, as incense is lit and local heads are respectfully bowed. Japanese schoolchildren come here to learn, and they sit in the shade of the trees at noon in civilised huddles, to eat lunch and chatter.

Many visit to reflect upon the atrocity of the bombing, but this attitude is not universal. I learned this during an encounter with an American man at the Ground Zero memorial, tucked away on a side-street beyond the boundaries of the park. We smiled at each other, as he shared his reasons for visiting, declared the power of the bomb to end the war, and the American soldiers, including his grandfather, whose lives were saved by this action. He was grateful for the bomb, but I was shocked at the way he had decided to make an emotional connection with this place.

However, the local community has a deep and profound connection to the park. Volunteers in distinctive uniforms meticulously maintain the place on a daily basis. This voluntary care of space escalates, as Hiroshima Peace Day draws near. Visit the park at 6am towards the end of July, and you will discover hordes of elderly people from the “Senior University”, wearing sunhats and brandishing trowels. They crouch above the ground, plucking weeds from the soil with gloved fingers. Whilst they garden, trails of elegantly dressed office workers bisect the park at intervals, carrying files and parasols in delicately gloved hands. Commuting to work, this stretch of land has become another familiar part of the rhythm of their daily lives.

There are also spaces of conflict and deviance here. The Uyoku dantai are the Japanese extreme-far right. They call themselves the Society of Patriots and travel about in dark vans painted with worrying slogans. War crime denialists, they support historical revisionism, oppose socialism and want Japan to join the nuclear circus. Unfortunately, they cannot be arrested due to the protection of freedom of ideology by the Constitution of Japan. So they jeer from the sidelines of the park, and organise protests outside the A-Dome on Hiroshima Peace Day. To the consternation of many, they have been gaining popularity in recent years.

However, there is also a place of joy hidden within this park, on a dusty corner of dry earth behind the public toilets. Here, a group of elderly Japanese men meet every week-day morning, to crouch on battered wooden chairs and play board games. Some, but not all, are Hibakusha, but all of them look relaxed, and laugh loudly as they engage in drawn-out battles of Shogi and Go. They have created their own friendly-yet-private space within this park. As dusk sets in, they pack up their board games and fold up their little chairs and tables to go home. The cicadas grow louder, and a calmness settles over the park as twilight descends. Small clusters of local teenagers gather and relax in the evening’s warmth. Faint sounds of conversation gradually dwindle to nothingness and the day draws to a close, reclaimed by the stillness of night. Our day in the park may be over, but the collective memory of the Hiroshima bombing forever remains.

With gratitude to Professor Bo Jacobs at Hiroshima Peace Institute, and with love to the extraordinary Hibakusha of Hiroshima and their families worldwide.

Becky Alexis-Martin is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Southampton, with expertise in the cultural and social effects of nuclear defence. She writes on the lives of nuclear test veteran families, and the cultural and social significance of nuclear places and spaces.

本貼文共有 0 個回覆

此貼文已鎖,將不接受回覆

| 發表文章 | 發起投票 |